Study finds lower sleeve volume after banded-LSG could be key to less weight recurrence vs. LSG

- owenhaskins

- Apr 24, 2023

- 5 min read

Sleeve volume could play a crucial role in lower rates of weight recurrence after banded laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (BLSG), compared to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), according to researchers from Egypt. Bariatric News spoke to the lead authors of the study, Professor Mohamed Hany from Alexandria University and Consultant of Bariatric Surgery at Madina Women’s Hospital, Alexandria, Egypt, who discussed the recent findings from the paper, ‘Comparison of Sleeve Volume Between Banded and Non‑banded Sleeve Gastrectomy: Midterm Effect on Weight and Food Tolerance - a Retrospective Study’, published in Obesity Surgery.

“The role of dilatation after sleeve gastrectomy is still uncertain it maybe an important cause of weight regain after the procedure. The loss of restriction allows more food intake and the subsequent weight regain can led to addition revisional surgery. Furthermore, up to 4.5% (1) of patients who had a sleeve gastrectomy require revisional surgery,” explained Professor Hany. “To our knowledge there were no published studies that have compared sleeve gastrectomy to banded sleeve gastrectomy in terms of sleeve volume, weight loss, weight regain and food tolerance (FT) over an intermediate follow-up period of four years.”

He said that one previous study concluded that sleeve dilatation might lead to weight recurrence with a four-fold increase in the main volume of the sleeve pouch, from 120ml to 524ml within five years of the procedure in patients who experience weight regain (2). In addition, additional studies revealed cases of weight regain after SG without sleeve pouch dilatation and others with doubling the sleeve pouch without WR but, these studies included small size and only followed up for 20–36 months (3-4).

“In our study we wanted to assess whether BLSG can add value by maintaining stomach volume and inhibiting weight regain by applying the Ring (MiniMizer Ring, Bariatric Solutions International) around the upper part of the sleeve pouch to preventing its expansion, with follow-up out to four years.”

For the study, Professor Hany and colleagues measured weight loss in terms of BMI, percentage of total weight loss and percentage of excess body weight loss at one-, two, three- and four-years. As well as weight recurrence (defined as: (1) as a 10% regain of the nadir weight at the last follow-up visit, (2)>10 kg above the nadir weight [5] and (3) BMI increase of≥5 kg/m2 above the nadir) at four years after surgery, and food tolerance using a questionnaire to assess the overall patient’s tolerance to food with a score ranging from 1 to 27 at one-, two, three- and four-years after surgery. Sleeve volume was assessed in all patients using an Multi-detector Computed Tomography (MDCT) virtual gastroscopy and 3D reconstruction at six months, one- and four-years after surgery.

Outcomes

In total, there were of 1,279 (83.7%) LSG patients and 132 (86.8%) banded-LSG patients who completed four years of follow-up and were included in the study. At baseline, the authors reported no significant differences between the two cohorts. The outcomes demonstrated an overall significant increase in the mean %TWL (p<0.002) and mean %EWL (p<0.001) at one-, two, three- and four-years after surgery from baseline. The significant interaction between change in mean %TWL and mean %EWL along post-operative follow-up period and type of surgery explained the greater increase in %TWL and %EWL among those who underwent BLSG than those who underwent LSG (p<0.043 and 0.047, respectively).

Regarding weight recurrence , for the LSG cohort weight recurrence occurred in 136 (10.6%) cases, and in four cases (3.1%) in the BLSG group according to the formula>10% above nadir. When the formula weight gain of>10 kg above the nadir was used, the LSG had 90 (7.0%) and BLSG zero (0.0%), and when the formula BMI increase of≥5 kg/m2 above the nadir, WR occurred in 31 (2.4%) cases in the LSG and zero (0.0%) in the BLSG cohort. Therefore, the authors reported weight regain was significantly higher in the LSG cohort (p<0.002) according to the first and second formulas, while for the third formula, there was no significant difference (p<0.07).

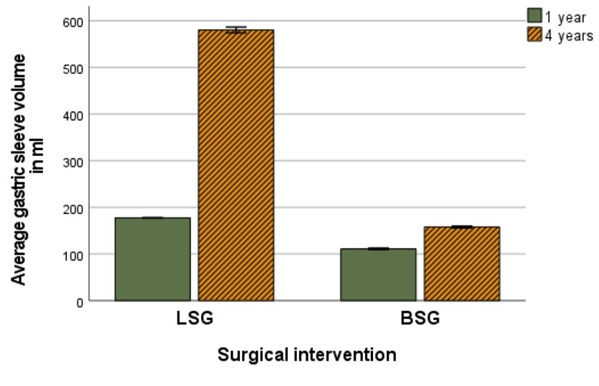

For food tolerance, there were significant improvements in both cohorts throughout follow-up (p<<0.001), with significantly less food tolerance in BLSG vs LSG group. The mean sleeve volume increased significantly in both cohorts throughout the follow-up (p.<0.001) and there was a greater increase in mean volume in the LSG cohort than in the BLSG cohort (p<0.001, Figure 1).

Professor Hany explained that less restriction gives a better food tolerance for LSG patients, but at the cost of lower weight loss and higher weight recurrence . Pre-operatively, GERD grade “A” was reported in 258 patients (20.2%) in the LSG cohort compared to 25 patients (18.9%) in the BLSG cohort (p<0.736). Postoperative routine endoscopy showed 21 patients (84%) in the BLSG group showed regression of the reflux, leading Professor Hany to suggest that “the ring may act as an anti-reflux device”.

Three patients (2.3%) in the BLSG group experienced solid dysphagia and reflux symptoms during the follow-up period caused by constriction at the ring site that was satisfactorily remedied with a few endoscopic pneumatic balloon dilation sessions.

“In my opinion, the outcomes showed better outcomes for patients who had BLSG compared to LSG, demonstrated by the fact no patients from the BLSG group needed conversion to another procedure, while 171 patients (13.4%) in the LSG had conversions to RYGB surgery. The indications for RYGB conversion were weight regain in 76 patients (3.9%), GERD in 64 patients (5.0%) and GERD with weight regain in 31 patients (2.2%).”

He added that as a retrospective study, this study is inherently inferior to prospective randomised controlled studies with possible undetected confounders or bias that was not corrected or measured. An additional limitation is the very small size of the BLSG group vs. the LSG group (ratio 1:10). Therefore, possible complications or findings that are less common could not be found in the BLSG group and he said larger studies are required to increase the power of the BLSG group.

“According to these results, we can offer BLSG to our patients but it is important to emphasise the important role of the multidisciplinary team to both manage patient expectations and issues around food intolerance. Each patient should be considered on a case by case basis when deciding the optimum procedure. This study also revealed we need additional studies to investigate whether the ring does have an inherent anti-reflux mechanism. Going forward, we need double blinded randomised controlled trials with significant numbers of patients in both LSG and BLSG groups to confirm some of the significant findings we have highlighted in our study.”

References

Yu Y, Klem ML, Kalarchian MA, Ji M, Burke LE. Predictors of weight regain after sleeve gastrectomy: an integrative review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15:995–1005.

Xu C, Yan T, Liu H, Mao R, Peng Y, Liu Y. Comparative safety and efectiveness of Rouxen-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy in obese elder patients: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Surg. 2020;30:3408–16

Braghetto I, Cortes C, Herquiñigo D, Csendes P, Rojas A, Mushle M, et al. Evaluation of the radiological gastric capacity and evolution of the BMI 2–3 years after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1262–9.

Langer F, Bohdjalian A, Felberbauer F, Fleischmann E, Reza Hoda M, Ludvik B, et al. Does gastric dilatation limit the success of sleeve gastrectomy as a sole operation for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:166–71.

Comments