Naturally occurring BRP molecule rivals semaglutide in weight loss but without side effects

- owenhaskins

- Mar 7

- 4 min read

Stanford University Medical Center researchers have identified a naturally occurring molecule, BRP, which appears similar to semaglutide in suppressing appetite and reducing body weight. Notably, testing in animals also showed that BRP worked without some semaglutide’s side effects such as nausea, constipation and significant loss of muscle mass. The newly discovered molecule, BRP, acts through a separate but similar metabolic pathway and activates different neurons in the brain, seemingly offering a more targeted approach to body weight reduction.

"The receptors targeted by semaglutide are found in the brain but also in the gut, pancreas and other tissues," said senior author of the research and assistant professor of pathology, Dr Katrin Svensson. "That's why Ozempic has widespread effects, including slowing the movement of food through the digestive tract and lowering blood sugar levels. In contrast, BRP appears to act specifically in the hypothalamus, which controls appetite and metabolism."

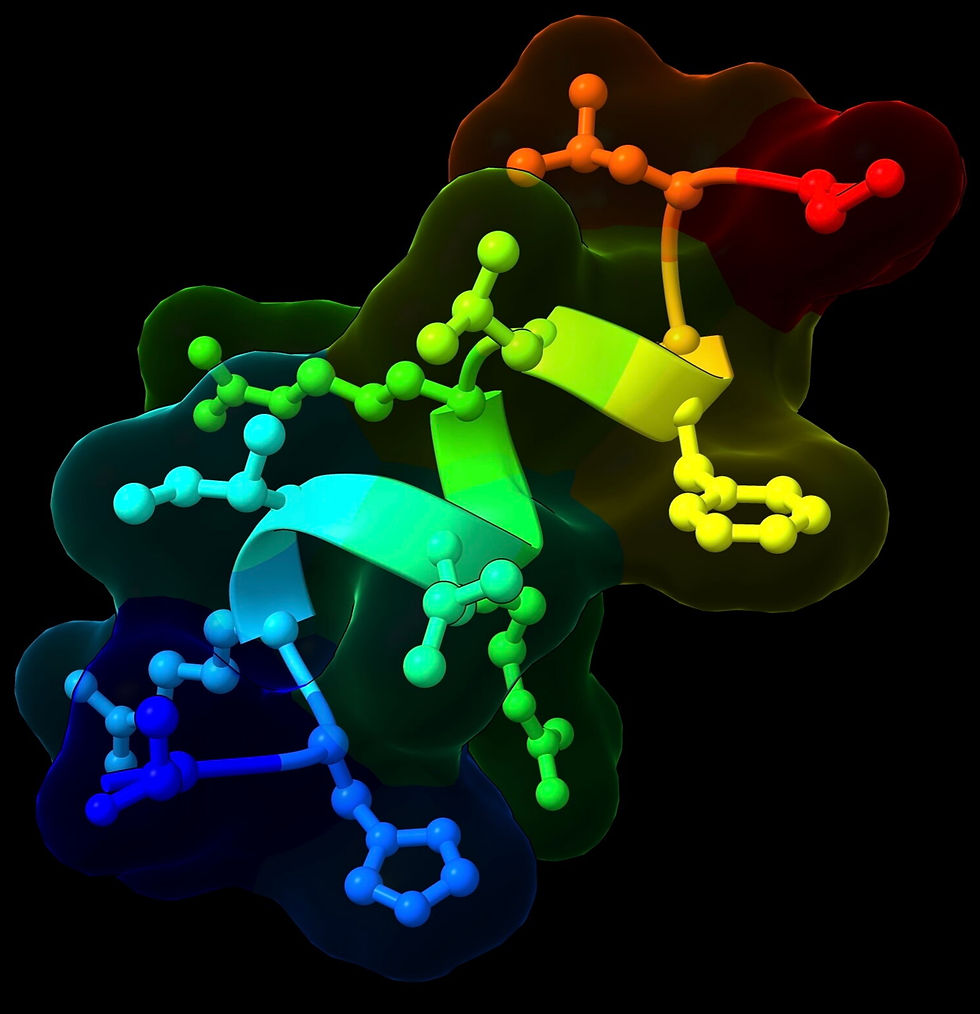

The study would not have been possible without the use of artificial intelligence to weed through dozens of proteins in a class called prohormones. Prohormones are biologically inert molecules that become active when they are cleaved by other proteins into smaller pieces called peptides; some of these peptides then function as hormones to regulate complex biological outcomes, including energy metabolism, in the brain and other organs.

Each prohormone can be divided in a variety of ways to create a plethora of functional peptide progeny. But with traditional methods of protein isolation, it's difficult to pick peptide hormones (which are relatively rare) out of the biological soup of the much more numerous natural byproducts of protein degradation and processing.

The researchers focused on the prohormone convertase 1/3 (also known as PCSK1/3), which separates prohormones at specific amino acid sequences and is known to be involved in human obesity.

One of the peptide products is glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which regulates appetite and blood sugar levels; semaglutide works by mimicking the effect of GLP-1 in the body. The team turned to artificial intelligence to help them identify other peptides involved in energy metabolism.

Peptide Predictor

Instead of manually isolating proteins and peptides from tissues and using techniques like mass spectrometry to identify hundreds of thousands of peptides, the researchers designed a computer algorithm they named ‘Peptide Predictor’ to identify typical prohormone convertase cleavage sites in all 20,000 human protein-coding genes.

They then focused on genes that encode proteins that are secreted outside the cell - a key characteristic of hormones - and that have four or more possible cleavage sites. Doing so, narrowed down the search to 373 prohormones, a manageable number to screen for their biological effects.

"The algorithm was absolutely key to our findings," Svensson said.

Peptide Predictor predicted that prohormone convertase 1/3 would generate 2,683 unique peptides from the 373 proteins. Senior research scientist and lead author of the study, Dr Laetitia Coassolo, and Svensson focused on sequences likely to be biologically active in the brain. They screened 100 peptides, including GLP-1, for their ability to activate lab-grown neuronal cells.

As expected, the GLP-1 peptide had a robust effect on the neuronal cells, increasing their activity threefold over control cells. But a small peptide made up of just 12 amino acids bumped up the cells' activity ten-fold over controls. The researchers named this peptide BRP based on its parent prohormone, BPM/retinoic acid inducible neural specific 2, or BRINP2 (BRINP2-related-peptide).

When the researchers tested the effect of BRP on lean mice and minipigs (which more closely mirror human metabolism and eating patterns than mice do), they found that an intramuscular injection of BRP prior to feeding reduced food intake over the next hour by up to 50% in both animal models.

Obese mice treated with daily injections of BRP for 14 days lost an average of 3 grams - due almost entirely to fat loss - while control animals gained about 3 grams over the same period. The mice also demonstrated improved glucose and insulin tolerance.

Behavioural studies of the mice and pigs found no differences in the treated animals' movements, water intake, anxiety-like behaviour or faecal production. And further studies of physiological and brain activity showed that BRP activates metabolic and neuronal pathways separate from those activated by GLP-1 or semaglutide.

The researchers hope to identify the cell-surface receptors that bind BRP and to further dissect the pathways of its action. They are also investigating how to help the peptide's effects last longer in the body to allow a more convenient dosing schedule if the peptide proves to be effective in regulating human body weight.

"The lack of effective drugs to treat obesity in humans has been a problem for decades," Svensson said. "Nothing we've tested before has compared to semaglutide's ability to decrease appetite and body weight. We are very eager to learn if it is safe and effective in humans."

Researchers from the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Minnesota; and the University of British Columbia contributed to the work.

Svensson and Coassolo are inventors on patents regarding BRP peptides for metabolic disorders. Svensson has co-founded a company called Merrifield Therapeutics, which plans to launch clinical trials of the molecule in humans in the near future.

The findings were featured in the paper, 'Prohormone cleavage prediction uncovers a non-incretin anti-obesity peptide', published in Nature. To access this paper, please click here (log-in maybe required)

Comentarios